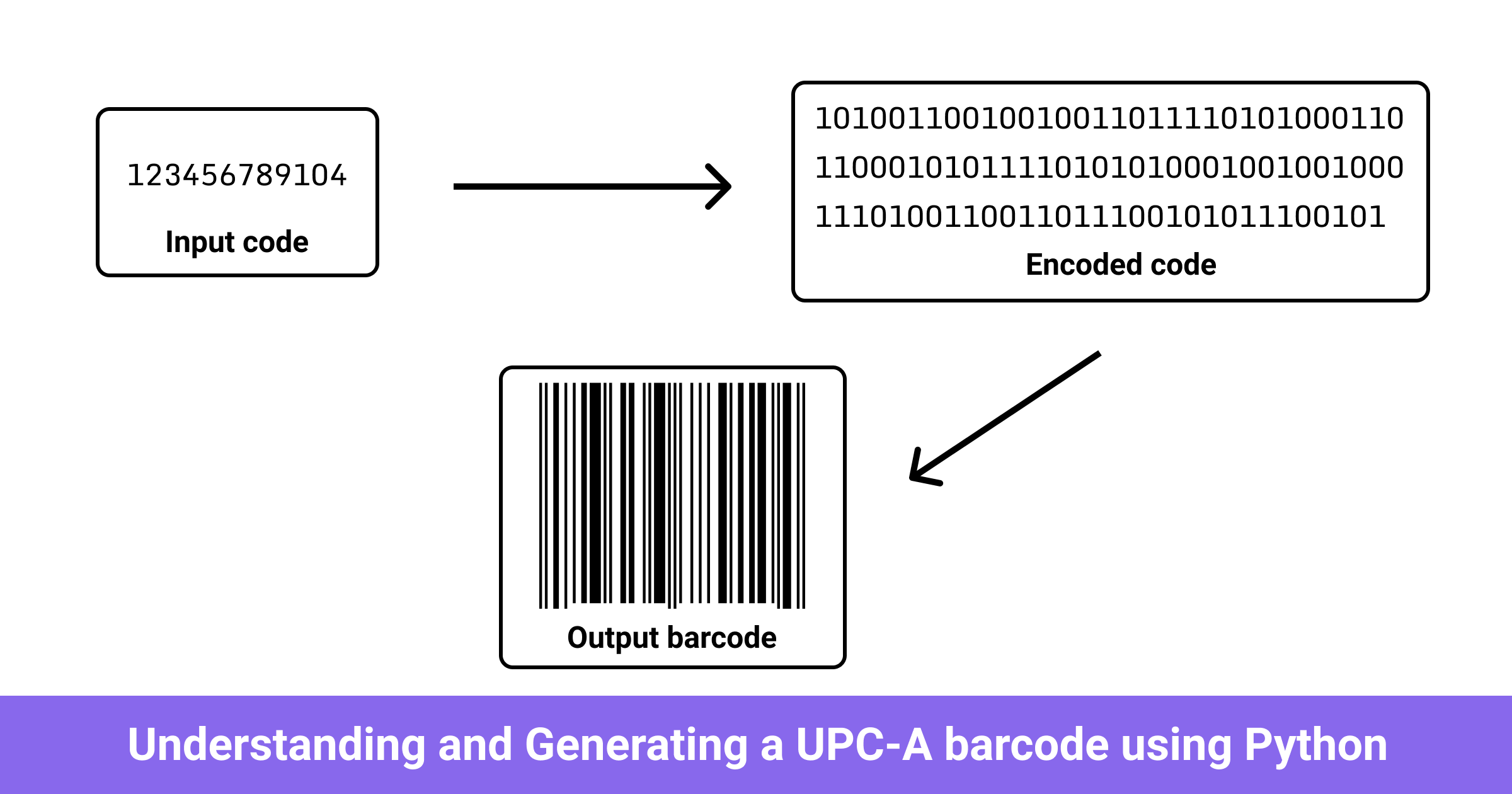

Understanding and Generating a UPC-A barcode using Python

Hi everyone! 👋 I have always been fascinated by barcodes and QR codes. I have known for a long time about how they work in theory but I never did enough research on it. It seemed like I would learn a lot from diving deeper and implementing a barcode generator from scratch. There is no substitute for learning more about something by creating it from scratch so that is exactly what I did.

This article is in a similar vein as my “Understanding and Decoding a JPEG Image using Python” article. I will take you on a guided tour of how a barcode works and how to create a super simple barcode generator for the Universal Product Code (UPC-A) using pure Python.

Disclaimer: I have borrowed some code and ideas from Hugo for this article.

History

It seems like barcodes have been there even before I was born. Turns out that is true. According to Wikipedia:

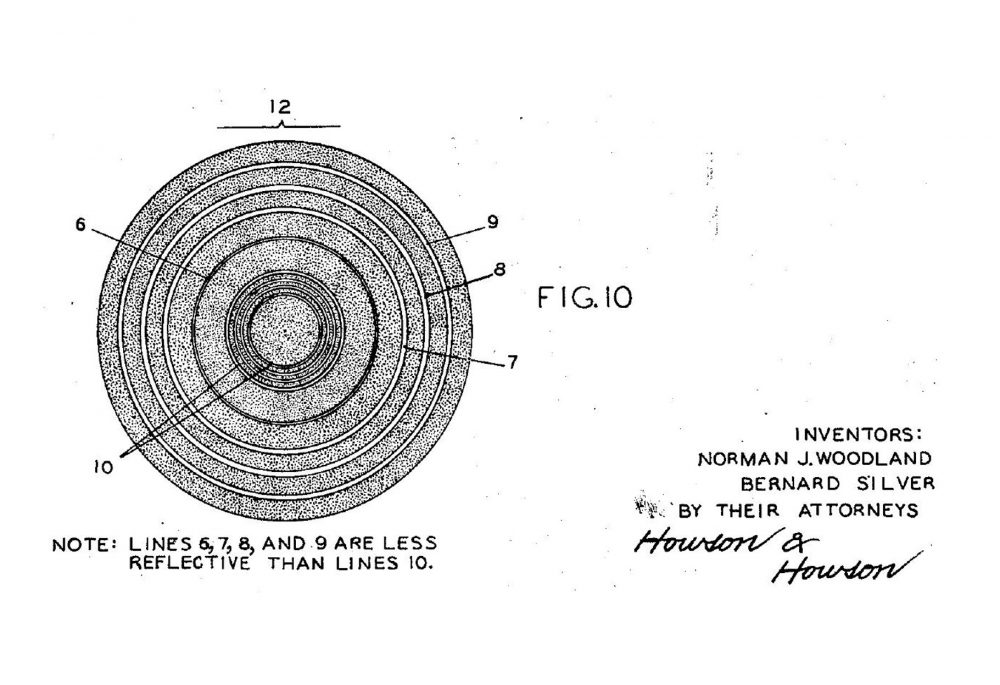

The barcode was invented by Norman Joseph Woodland and Bernard Silver and patented in the US in 1951. The invention was based on Morse code that was extended to thin and thick bars. However, it took over twenty years before this invention became commercially successful.

The idea for an automated entry system (barcode) originated when a Drexel student overheard a food chain owner asking for a system to automatically read product information during checkout. No doubt the barcode later found huge commercial success in the retail industry!

The idea for encoding this information in the form of bars originated from morse code. One of the early versions just extended the dots to form vertical lines. The follow-up versions included a bunch of fun types of barcodes. There was also a proposal for a circular bullseye barcode in the early days. A major reason they didn’t stay for long is that the printers would sometimes smear the ink and that would render the code unreadable. However, printing vertical bars meant that the smears would only increase the bar height and the code would still be readable.

Typical barcode

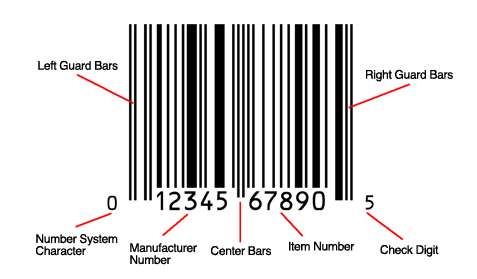

A typical barcode usually contains:

- Left guard bars

- Center bars

- Right guard bars

- Check digit

- Actual information between the guards

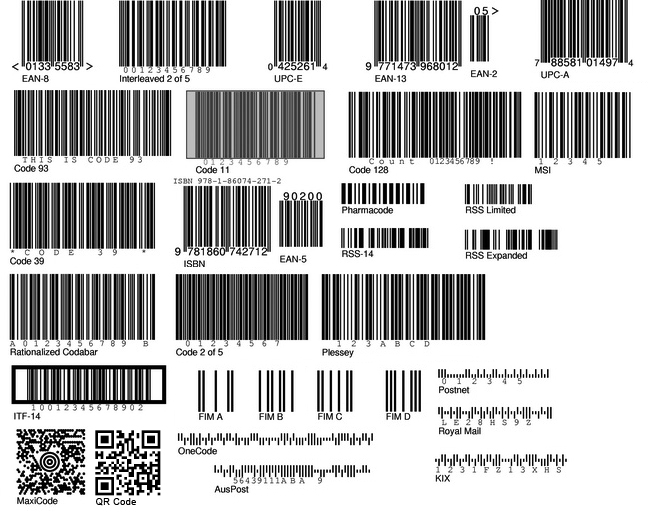

The way the information is encoded in a barcode is called the symbology. Some symbologies allow storing alphabets but some only allow storing digits. There are tons of different symbologies out there and each is prevalent in a different industry.

UPC-A

In this article, we will be focusing on the UPC-A barcode. This is type A of the Universal Product Code barcode. It only allows storing digits (0-9) in the bars. I chose it for this article because it is super simple and quite a few other codes are just an extension of this.

The symbology for UPC-A only allows storing 12 digits. The first digit, Number System Character, decides how the rest of the digits in the barcode will be interpreted. For example, If it is a 0, 1, 6, 7, or 8, it is going to be interpreted as a typical retail product. If it starts with a 2 then it is going to be interpreted as a produce item that contains a weight or price. The next 10 digits represent product-specific information and the interpretation depends on the NSC. The last digit is a check digit and helps detect certain errors in the barcode.

We will try to create a UPC-A barcode using pure Python. I will not add the digits to the SVG but that would be a simple extension once we have the main barcode generation working.

You can get more information about UPC and other forms of barcodes from Wikipedia.

Check digit calculation

The check digit allows the barcode reader to detect certain errors that might have been introduced into the barcode for various reasons. Each symbology uses a specific formula for calculating the check digit. The check digit equation for UPC-A looks like this:

Here x_1 is the first digit of UPC and x_12 is the check digit itself that is unknown. The steps for calculating the check digit are:

- Sum all odd-numbered positions (1,3,5…)

- Multiply the sum by 3

- Sum all even-numbered positions (2,4,6…) and add them to the result from step 2

- Calculate the result from step 3 modulo 10

- If the result from step 4 is 0 then the check digit is 0. Otherwise check digit is 10 - result from step 4

This error-check algorithm is known as the Luhn algorithm. It is one of the many different error detection algorithms out there.

Barcode encoding

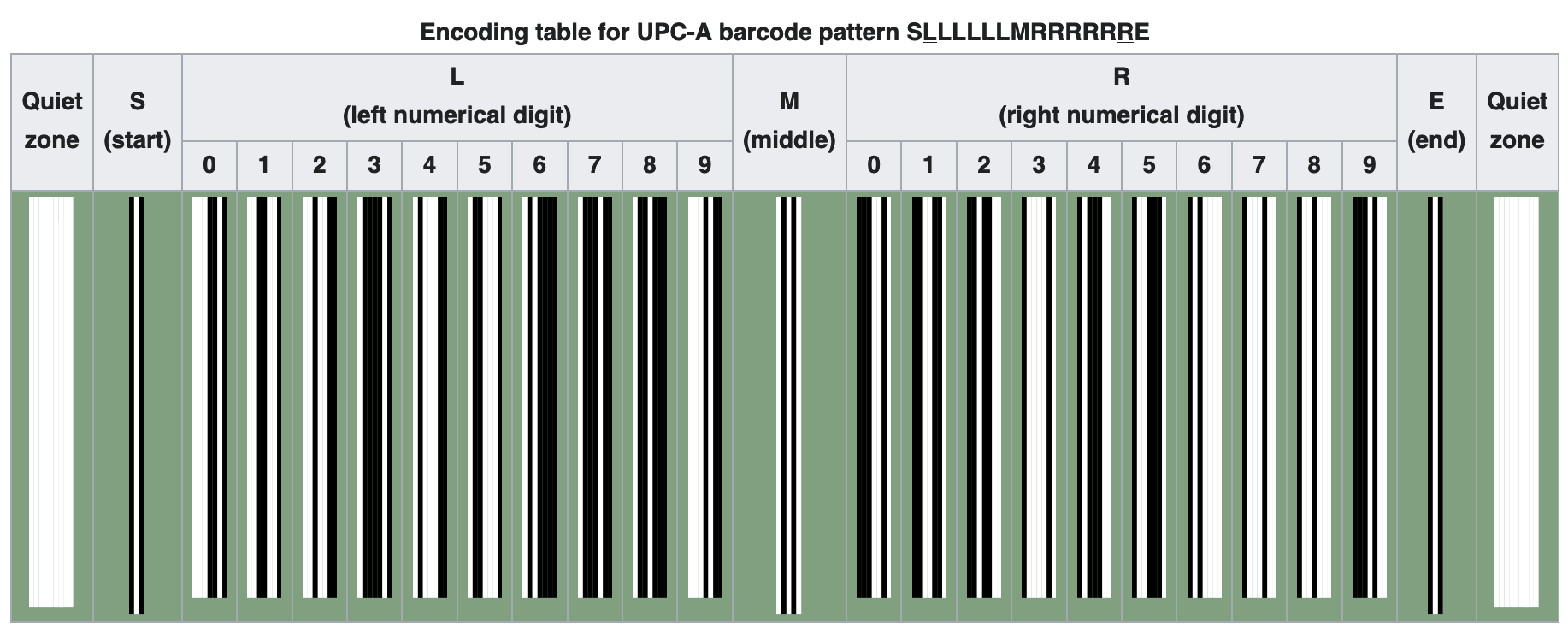

Wikipedia provides very good visualization for what the barcode encoding looks like for UPC-A. There are two sets of digits that are divided by a middle guard. Each digit is encoded by 7 vertical lines or modules. Each of these can be either black or white. For example, 0 is encoded as WWWBBWB.

The digits from 0-9 are encoded slightly differently on the left side of M (middle guard) vs the right side. A fun fact is that the right side encoding of a digit is an optical inverse of its left side encoding. For example, the 1 on the left side is encoded as WWBBWWB and the 1 on the right side is encoded as BBWWBBW. A reason for this is that this allows barcode readers to figure out if they are scanning the barcode in the correct direction or not. Some scanners would do two passes, once reading from left to right and once from right to left and some would simply reverse the input data without a second pass if it started scanning from the wrong direction.

The whole visual representation of the barcode is divided into the following parts and unique patterns of black and white vertical lines (also known as modules):

| Position | Element | Count | Module width |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quiet zone | 1 | 9 modules (all white) |

| 2 | Start guard bar | 1 | 3 modules (BWB) |

| 3 | Left digit | 6 | 7 modules (variable) |

| 4 | Mid guard bar | 1 | 5 modules (WBWBW) |

| 5 | Right digit | 5 | 7 modules (variable) |

| 6 | Check digit | 1 | 7 modules (variable) |

| 7 | End guard bar | 1 | 3 modules (BWB) |

| 8 | Quiet zone | 1 | 9 modules (all white) |

There are a total of 113 modules or 113 black+white lines in a UPC-A barcode.

Defining encoding table

The very first step in creating our custom barcode generator is to define the encoding table for the digits and the guard bars. Start by creating a new barcode_generator.py file and adding this code to it:

class UPC:

"""

The all-in-one class that represents the UPC-A

barcode.

"""

EDGE = "101"

MIDDLE = "01010"

CODES = {

"L": (

"0001101",

"0011001",

"0010011",

"0111101",

"0100011",

"0110001",

"0101111",

"0111011",

"0110111",

"0001011",

),

"R": (

"1110010",

"1100110",

"1101100",

"1000010",

"1011100",

"1001110",

"1010000",

"1000100",

"1001000",

"1110100",

),

}

SIZE = "{0:.3f}mm"

TOTAL_MODULES = 113

MODULE_WIDTH = 0.33

MODULE_HEIGHT = 25.9

EXTENDED_MODULE_HEIGHT = MODULE_HEIGHT + 5*MODULE_WIDTH

BARCODE_WIDTH = TOTAL_MODULES * MODULE_WIDTH

BARCODE_HEIGHT = EXTENDED_MODULE_HEIGHT

def __init__(self, upc):

self.upc = list(str(upc))[:11]

if len(self.upc) < 11:

raise Exception(f"The UPC has to be of length 11 or 12 (with check digit)")

Here we are creating an all-in-one class and defining some class variables and the mapping between digits and the black/white lines (modules). The 1 represents black and 0 represents white. EDGE represents the start and end guards. MIDDLE represents the middle guard. CODES dictionary contains two tuples mapped to L and R for the left and right digits. The index position in the tuple represents the digit we are mapping. For example, the first element of the L tuple represents the 0 digit that is encoded to WWWBBWB or 0001101.

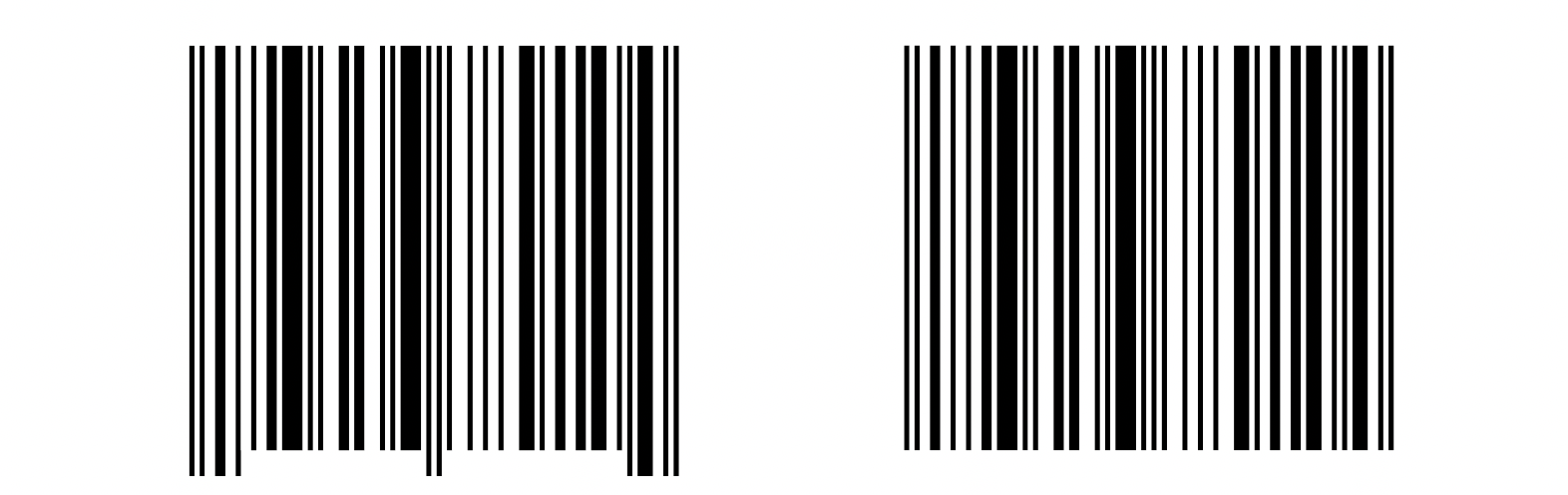

The MODULE_WIDTH and the other sizes are all taken from Wikipedia. These are the dimensions of a typical UPC-A barcode in the normal sizing. You can tweak these sizes to an extent and the barcode should still work fine. The EXTENDED_MODULE_HEIGHT refers to the height of the modules or bars for the three guards (L, M, R) and the first and last digit (check digit) of the UPC. These modules are generally taller than the other modules. This extended height is also taken from Wikipedia. The barcode is still valid without this height difference but it looks nice with this height difference and shows a clear separation of the left and right digits. For example, compare these two barcodes:

I find the left barcode cleaner and nicer than the right one. I can clearly tell where the digits are being divided by a middle guard.

I also added an __init__ method that takes the upc as input and throws an Exception if the size is smaller than 11. I haven’t added code for verifying the total length because I am truncating it to the first 11 digits. We will add the 12th check digit ourselves. The input upc can be any integer up to a length of 11 digits. We don’t care about NSC and what the code actually represents.

Check digit & error detection

Let’s implement the error detection and check digit calculation to our class. We will use the same formula we talked about earlier:

class UPC:

# ...

def calculate_check_digit(self):

"""

Calculate the check digit

"""

upc = [int(digit) for digit in self.upc[:11]]

oddsum = sum(upc[::2])

evensum = sum(upc[1::2])

check = (evensum + oddsum * 3) % 10

if check == 0:

return [0]

else:

return [10 - check]

I am using list slicing to get the even and odd digit positions and then doing some arithmetic for the check digit calculation. It might have been better to let the user input the check digit and then compare that to our calculated check digit and make sure the entered barcode is correct. It would have made the barcode entry more robust but I will leave that error detection up to you.

Encoding UPC

Let’s add a new method to encode the UPC to the 01 mapping we defined in our class. The code will look something like this:

class UPC:

# ...

def __init__(self, upc):

self.upc = list(str(upc))[:11]

if len(self.upc) < 11:

raise Exception(f"The UPC has to be of length 11 or 12 (with check digit)")

self.upc = self.upc + self.calculate_check_digit()

encoded_code = self.encode()

def encode(self):

"""

Encode the UPC based on the mapping defined above

"""

code = self.EDGE[:]

for _i, number in enumerate(self.upc[0:6]):

code += self.CODES["L"][int(number)]

code += self.MIDDLE

for number in self.upc[6:]:

code += self.CODES["R"][int(number)]

code += self.EDGE

self.encoded_upc = code

The encode method simply loops over the UPC and creates a corresponding string containing a pattern of 0 and 1 based on each digit in the UPC. It appropriately uses the L and R mapping depending on whether the UPC digit being iterated on is in the first half of UPC or the second. It also adds the three guard bars at the correct places.

For example, it will turn 123456789104 into 10100110010010011011110101000110110001010111101010100010010010001110100110011011100101011100101

I also modified the __init__ method to make use of the newly created encode method.

Generating base SVG

We will be outputting an SVG from our code. The way SVGs work is somewhat similar to HTML. They also contain a bunch of tags that you might have seen in an HTML document. An SVG will start with an XML tag and a DOCTYPE. This will be followed by an svg tag that contains all the meat of our SVG. In this SVG we will group everything in a g (group) tag. In this group tag, we will define the different modules (vertical bars) as a rect.

Putting everything in a group just makes vector graphic editors (Inkscape, Illustrator, etc) play nicely with the generated SVGs.

A simple SVG looks something like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg

PUBLIC '-//W3C//DTD SVG 1.1//EN'

'http://www.w3.org/Graphics/SVG/1.1/DTD/svg11.dtd'>

<svg version="1.1" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" width="44.000mm" height="23.000mm">

<g id="barcode_group">

<rect width="100%" height="100%" style="fill:white"/>

<rect x="6.500mm" y="1.000mm" width="0.330mm" height="15.000mm" style="fill:black;"/>

<rect x="6.830mm" y="1.000mm" width="0.330mm" height="15.000mm" style="fill:white;"/>

<rect x="7.160mm" y="1.000mm" width="0.330mm" height="15.000mm" style="fill:black;"/>

<!-- truncated -->

</g>

</svg>

Even on a cursory look, it is fairly easy to imagine what this SVG code will visually look like.

Let’s add some code to our class to generate a skeleton/boilerplate SVG that we can later fill in:

import xml.dom

class UPC:

# ...

def __init__(self, upc):

# ...

self.create_barcode()

def create_barcode(self):

self.prepare_svg()

def prepare_svg(self):

"""

Create the complete boilerplate SVG for the barcode

"""

self._document = self.create_svg_object()

self._root = self._document.documentElement

group = self._document.createElement("g")

group.setAttribute("id", "barcode_group")

self._group = self._root.appendChild(group)

background = self._document.createElement("rect")

background.setAttribute("width", "100%")

background.setAttribute("height", "100%")

background.setAttribute("style", "fill: white")

self._group.appendChild(background)

def create_svg_object(self):

"""

Create an SVG object

"""

imp = xml.dom.getDOMImplementation()

doctype = imp.createDocumentType(

"svg",

"-//W3C//DTD SVG 1.1//EN",

"http://www.w3.org/Graphics/SVG/1.1/DTD/svg11.dtd",

)

document = imp.createDocument(None, "svg", doctype)

document.documentElement.setAttribute("version", "1.1")

document.documentElement.setAttribute("xmlns", "http://www.w3.org/2000/svg")

document.documentElement.setAttribute(

"width", self.SIZE.format(self.BARCODE_WIDTH)

)

document.documentElement.setAttribute(

"height", self.SIZE.format(self.BARCODE_HEIGHT)

)

return document

def create_module(self, xpos, ypos, width, height, color):

"""

Create a module and append a corresponding rect to the SVG group

"""

element = self._document.createElement("rect")

element.setAttribute("x", self.SIZE.format(xpos))

element.setAttribute("y", self.SIZE.format(ypos))

element.setAttribute("width", self.SIZE.format(width))

element.setAttribute("height", self.SIZE.format(height))

element.setAttribute("style", "fill:{};".format(color))

self._group.appendChild(element)

We are doing a couple of things here. Let’s look at each method one by one.

__init__: I modified it to make use of thecreate_barcodemethodcreate_barcode: For now it simply calls theprepare_svgmethod. We will soon update it to do more stuffprepare_svg: Callscreate_svg_objectto create a skeleton SVG object and then adds a group to store our barcode and a white rectangle inside that said group. This white rectangle will act as the background of our barcode.create_svg_object: Uses thexml.dompackage to set up a DOM with proper doctype and attributescreate_module: I am not currently using it. It is going to create arectfor each black/white bar with the appropriate size and style and append that to our SVG.

Packing the encoded UPC

We can use the encoded UPC and the SVG generation code we have so far to create an SVG but let’s create one more method to pack the encoded UPC. Packing means that it will turn a group of 0s and 1s into a single digit. For example:

"001101" -> [-2, 2, -1, 1]

The digit value tells us how many same characters it saw before coming across a different character. And if the digit is negative then we know that it is referring to a 0 and if it is positive then we know it is referring to a 1. This will help us in figuring out what color to use to create the corresponding rectangle (black vs white).

The benefit of packing is that instead of creating 6 rectangles for 001101, we can only create 4 rectangles with varying widths. In total, we will only have to make 59 rectangles or bars (3 + 3 + 5 for the guards and 4*12 for the 12 digits). The packing code would look like this:

class UPC:

# ...

def packed(self, encoded_upc):

"""

Pack the encoded UPC to a list. Ex:

"001101" -> [-2, 2, -1, 1]

"""

encoded_upc += " "

extended_bars = [1,2,3, 4,5,6,7, 28,29,30,31,32, 53,54,55,56, 57,58,59]

count = 1

bar_count = 1

for i in range(0, len(encoded_upc) - 1):

if encoded_upc[i] == encoded_upc[i + 1]:

count += 1

else:

if encoded_upc[i] == "1":

yield count, bar_count in extended_bars

else:

yield -count, bar_count in extended_bars

bar_count += 1

count = 1

I have also added an extended_bars list. This contains the (1 numbered) indices of bars that should be extended (the three guards and the first and last digit).

Creating the barcode SVG

Let’s edit the create_barcode method to generate the full SVG code for our UPC-A barcode:

class UPC:

# ...

def create_barcode(self):

self.prepare_svg()

# Quiet zone is automatically added as the background is white We will

# simply skip the space for 9 modules and start the guard from there

x_position = 9 * self.MODULE_WIDTH

for count, extended in self.packed(self.encoded_upc):

if count < 0:

color = "white"

else:

color = "black"

config = {

"xpos": x_position,

"ypos": 1,

"color": color,

"width": abs(count) * self.MODULE_WIDTH,

"height": self.EXTENDED_MODULE_HEIGHT if extended else self.MODULE_HEIGHT,

}

self.create_module(**config)

x_position += abs(count) * self.MODULE_WIDTH

We first prepare the skeleton of the SVG. Then we skip 9 module widths. This is the quiet zone that is required for the barcode scanners to accurately identify a barcode. It is at least 9 module widths according to Wikipedia and exists on either side of the barcode. Our background is already white so we don’t have to draw any rectangle to represent the quiet zone.

Then we loop over the packed encoding. For each return value from the packed method, we calculate the width and height of the rectangle. The calculation is simple. For the width, we take the absolute value of count and multiply that with MODULE_WIDTH. For the height, if extended is True we set it to EXTENDED_MODULE_HEIGHT, otherwise, we set it to MODULE_HEIGHT. After creating a dictionary with this config, we pass it to create_module. At the end of each loop, we adjust the x position of the next rectangle based on how wide the current rectangle is.

Note: The ** in self.create_module(**config) converts the items in the config dict into keyword arguments.

Saving the SVG

The only two things left now are a method to dump the SVG code to a file and to tie everything together in the __init__ method. Let’s first add a save method:

import os

class UPC:

# ...

def save(self, filename):

"""

Dump the final SVG XML code to a file

"""

output = self._document.toprettyxml(

indent=4 * " ", newl=os.linesep, encoding="UTF-8"

)

with open(filename, "wb") as f:

f.write(output)

xml.dom provides us with a nice toprettyxml method to dump a nicely formatted XML document into a string which we can then save to a file.

Let’s finish the code by modifying the __init__ method and adding some driver code at the end of the file:

class UPC:

# ...

def __init__(self, upc):

self.upc = list(str(upc))[:11]

if len(self.upc) < 11:

raise Exception(f"The UPC has to be of length 11 or 12 (with check digit)")

self.upc = self.upc + self.calculate_check_digit()

encoded_code = self.encode()

self.create_barcode()

self.save("upc_custom.svg")

# ...

if __name__ == "__main__":

upc = UPC(12345678910)

Save the file and try running it. It should generate a upc_custom.svg file in the same directory as your Python code.

Complete code

The complete code is available below and on GitHub:

import xml.dom

import os

class UPC:

"""

The all-in-one class that represents the UPC-A

barcode.

"""

QUIET = "000000000"

EDGE = "101"

MIDDLE = "01010"

CODES = {

"L": (

"0001101",

"0011001",

"0010011",

"0111101",

"0100011",

"0110001",

"0101111",

"0111011",

"0110111",

"0001011",

),

"R": (

"1110010",

"1100110",

"1101100",

"1000010",

"1011100",

"1001110",

"1010000",

"1000100",

"1001000",

"1110100",

),

}

SIZE = "{0:.3f}mm"

MODULE_WIDTH = 0.33

MODULE_HEIGHT = 25.9

EXTENDED_MODULE_HEIGHT = MODULE_HEIGHT + 5*MODULE_WIDTH

BARCODE_HEIGHT = EXTENDED_MODULE_HEIGHT

TOTAL_MODULES = 113

def __init__(self, upc):

self.upc = list(str(upc))[:11]

if len(self.upc) < 11:

raise Exception(f"The UPC has to be of length 11 or 12 (with check digit)")

self.upc = self.upc + self.calculate_check_digit()

encoded_code = self.encode()

self.create_barcode()

self.save("upc_custom.svg")

def calculate_check_digit(self):

"""

Calculate the check digit

"""

upc = [int(digit) for digit in self.upc[:11]]

oddsum = sum(upc[::2])

evensum = sum(upc[1::2])

check = (evensum + oddsum * 3) % 10

if check == 0:

return [0]

else:

return [10 - check]

def encode(self):

"""

Encode the UPC based on the mapping defined above

"""

code = self.EDGE[:]

for _i, number in enumerate(self.upc[0:6]):

code += self.CODES["L"][int(number)]

code += self.MIDDLE

for number in self.upc[6:]:

code += self.CODES["R"][int(number)]

code += self.EDGE

self.encoded_upc = code

def create_barcode(self):

self.prepare_svg()

# Quiet zone is automatically added as the background is white We will

# simply skip the space for 9 modules and start the guard from there

x_position = 9 * self.MODULE_WIDTH

for count, extended in self.packed(self.encoded_upc):

if count < 0:

color = "white"

else:

color = "black"

config = {

"xpos": x_position,

"ypos": 1,

"color": color,

"width": abs(count) * self.MODULE_WIDTH,

"height": self.EXTENDED_MODULE_HEIGHT if extended else self.MODULE_HEIGHT,

}

self.create_module(**config)

x_position += abs(count) * self.MODULE_WIDTH

def packed(self, encoded_upc):

"""

Pack the encoded UPC to a list. Ex:

"001101" -> [-2, 2, -1, 1]

"""

encoded_upc += " "

extended_bars = [1,2,3, 4,5,6,7, 28,29,30,31,32, 53,54,55,56, 57,58,59]

count = 1

bar_count = 1

for i in range(0, len(encoded_upc) - 1):

if encoded_upc[i] == encoded_upc[i + 1]:

count += 1

else:

if encoded_upc[i] == "1":

yield count, bar_count in extended_bars

else:

yield -count, bar_count in extended_bars

bar_count += 1

count = 1

def prepare_svg(self):

"""

Create the complete boilerplate SVG for the barcode

"""

self._document = self.create_svg_object()

self._root = self._document.documentElement

group = self._document.createElement("g")

group.setAttribute("id", "barcode_group")

self._group = self._root.appendChild(group)

background = self._document.createElement("rect")

background.setAttribute("width", "100%")

background.setAttribute("height", "100%")

background.setAttribute("style", "fill: white")

self._group.appendChild(background)

def create_svg_object(self):

"""

Create an SVG object

"""

imp = xml.dom.getDOMImplementation()

doctype = imp.createDocumentType(

"svg",

"-//W3C//DTD SVG 1.1//EN",

"http://www.w3.org/Graphics/SVG/1.1/DTD/svg11.dtd",

)

document = imp.createDocument(None, "svg", doctype)

document.documentElement.setAttribute("version", "1.1")

document.documentElement.setAttribute("xmlns", "http://www.w3.org/2000/svg")

document.documentElement.setAttribute(

"width", self.SIZE.format(self.TOTAL_MODULES * self.MODULE_WIDTH)

)

document.documentElement.setAttribute(

"height", self.SIZE.format(self.BARCODE_HEIGHT)

)

return document

def create_module(self, xpos, ypos, width, height, color):

"""

Create a module and append a corresponding rect to the SVG group

"""

element = self._document.createElement("rect")

element.setAttribute("x", self.SIZE.format(xpos))

element.setAttribute("y", self.SIZE.format(ypos))

element.setAttribute("width", self.SIZE.format(width))

element.setAttribute("height", self.SIZE.format(height))

element.setAttribute("style", "fill:{};".format(color))

self._group.appendChild(element)

def save(self, filename):

"""

Dump the final SVG XML code to a file

"""

output = self._document.toprettyxml(

indent=4 * " ", newl=os.linesep, encoding="UTF-8"

)

with open(filename, "wb") as f:

f.write(output)

if __name__ == "__main__":

upc = UPC(12345678910)

Conclusion

Thank you so much for reading this article. I know it was fairly long so thanks for sticking around. If you enjoyed this article and would love to see a much more cleaner implementation of barcode generator in Python, I recommend you check out this repo. I have shamelessly borrowed ideas and code from Hugo’s repo for this article. It contains implementations for other barcode formats as well such as the EAN13 (EuropeanArticleNumber13) and JapanArticleNumber.

If you want to read more about barcodes, Peter has written a wonderful post about Spotify codes work.

I really enjoyed diving deeper into barcodes and learning more about their history and implementation. This is a very fascinating field and I do plan on exploring it more in the future. I will probably try to tackle QR codes next as they are slowly replacing barcodes everywhere and can encode a lot more information in a much smaller space. It would be fun to try and implement a QR code generator in Python.

Next steps

If you want to continue working on this, you are more than welcome to copy and modify my code. I am releasing it under the MIT license. A couple of things you can add are:

- Add support for text underneath the barcode

- Add support for more symbology

- Add stricter error checking

- Add a PNG/JPG output

I hope you enjoyed reading this article. If you have any questions, comments, suggestions, or feedback, please write a comment below or send me an email. I would love to hear from you.

Take care ❤️👋

✍️ Comments

Thank you!

Your comment has been submitted and will be published once it has been approved. 😊

OK