Reverse Engineering Nike Run Club Android App Using Frida

Hi everyone! 👋 If you have been following my blog then you might have already read the article on reverse engineering an Android app by writing custom smali code. I am still very much a reverse engineering beginner so after that article, I got to learn about Frida. I was told that Frida is much faster and a lot easier for scenarios where I want to snoop on functions. Well, I am glad to report that all the suggestions were absolutely correct.

In this article, I will share some details about how I was able to use it to snoop around the Nike Run Club Android app. The final goal was to extract authentication tokens that Nike generates when you log-in. This was another project on the backburner and what better way to get a project off the back burner by learning something new?

Backstory

I am an avid runner. Most of my friends and family know that. When I started this sport I got hooked to Nike Run Club. I used to diligently record each run so that I had a record for all my runs. This went on for 2 years until I found out that most of my new running friends were using Strava. I decided to move over to Strava but was pretty bummed by the lack of data export options in NRC.

There were documents online about the Nike API and they allowed you to also export your data in the JSON format but I wanted something a bit more automated. Therefore, I decided to do what any other insane person would do and started my journey of reverse-engineering the Nike Run Club APK. I decided to go to the source and figure out if I could reverse engineer the login process and generate tokens in a completely automated fashion.

This article will teach you the basic usage of Frida and how you too can go ahead and snoop around different APKs. But before we go to that part, you need to know how I ended up deciding to reverse engineer the app and not simply do a MITM attack using mitmproxy.

Intercept NRC traffic

When I started the project, I decided to snoop the traffic using mitmproxy. You can download the NRC APK from APKMirror to follow along. After downloading it, rename it to nike.apk so that the rest of the commands in this tutorial are version agnostic.

Next, you can use adb to install this APK on the emulator:

$ adb install nike.apk

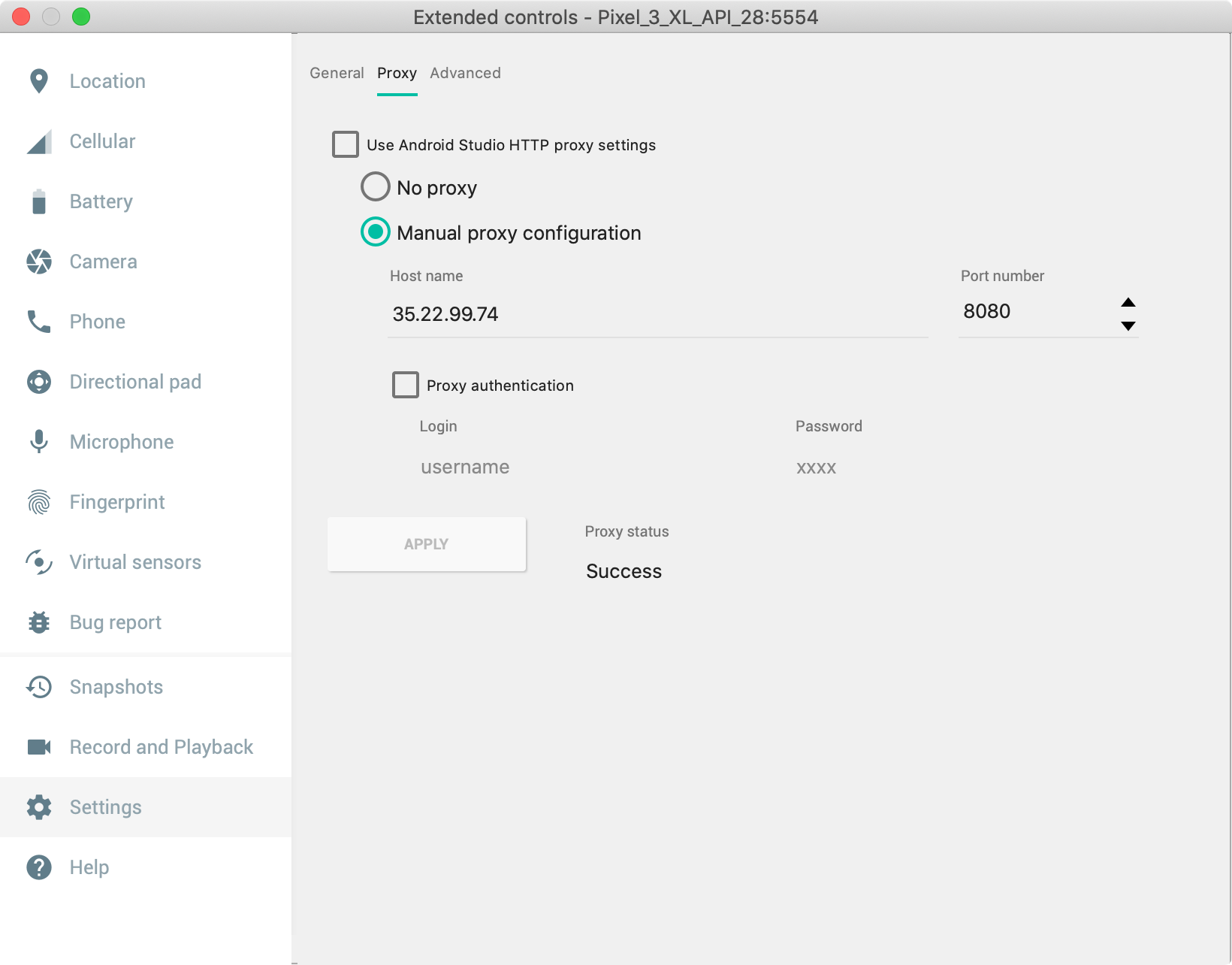

Now, you need to run mitmproxy. If you struggle with setting up an emulator or the proxy, refer to this previous article of mine where I go in slightly more detail about how to do these things. I used the following command to run mitmproxy:

$ mitmproxy --set block_global=false --showhost

The last thing to do is to install mitmproxy system certificates on the Android emulator by following the official docs and point the emulator to your local mitmproxy instance.

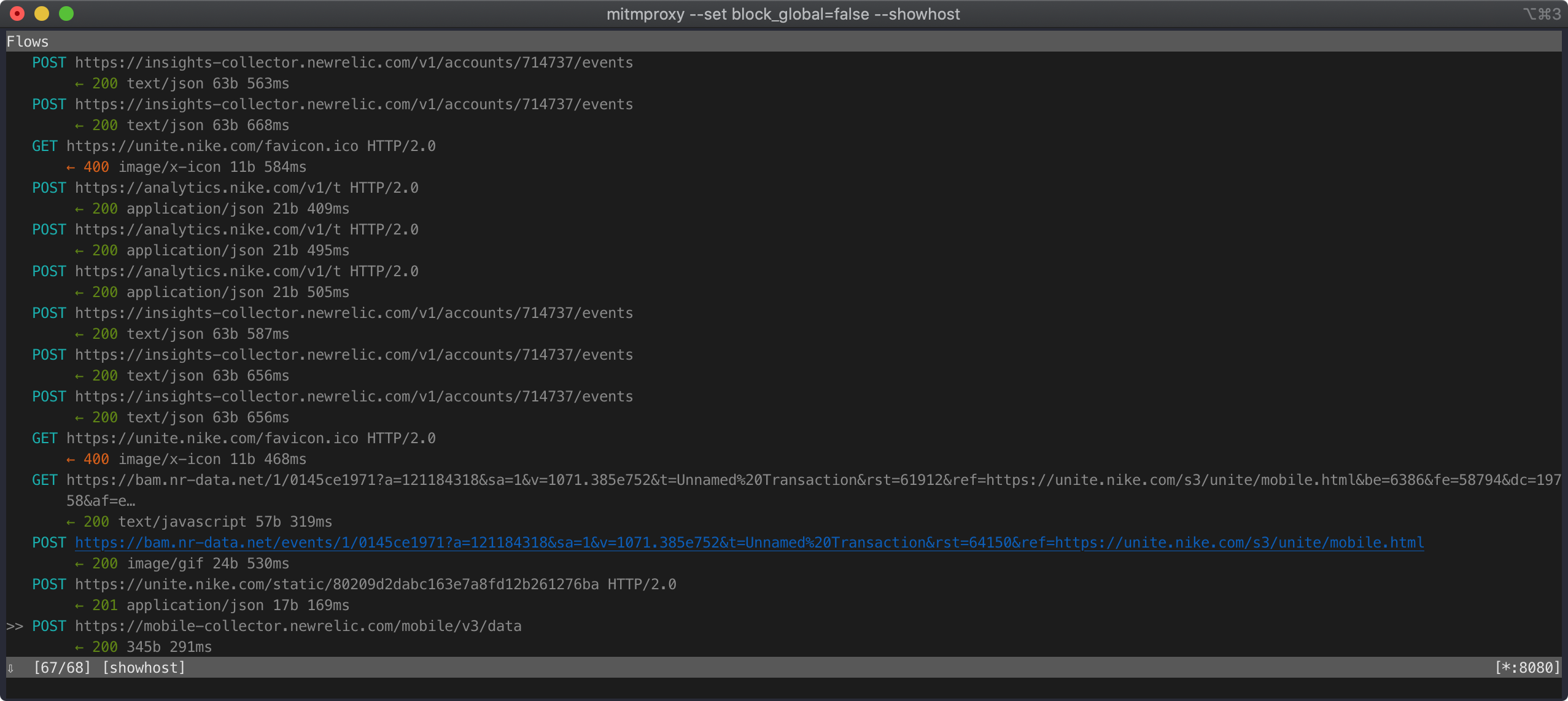

After this setup, I opened up NRC and started checking out the requests in mitmproxy. I was kinda surprised and pretty spooked by the number of analytics requests NRC was sending. There was no SSL pinning in place so I didn’t have to do anything special before all requests started showing up. All these 68 requests were before I even signed in:

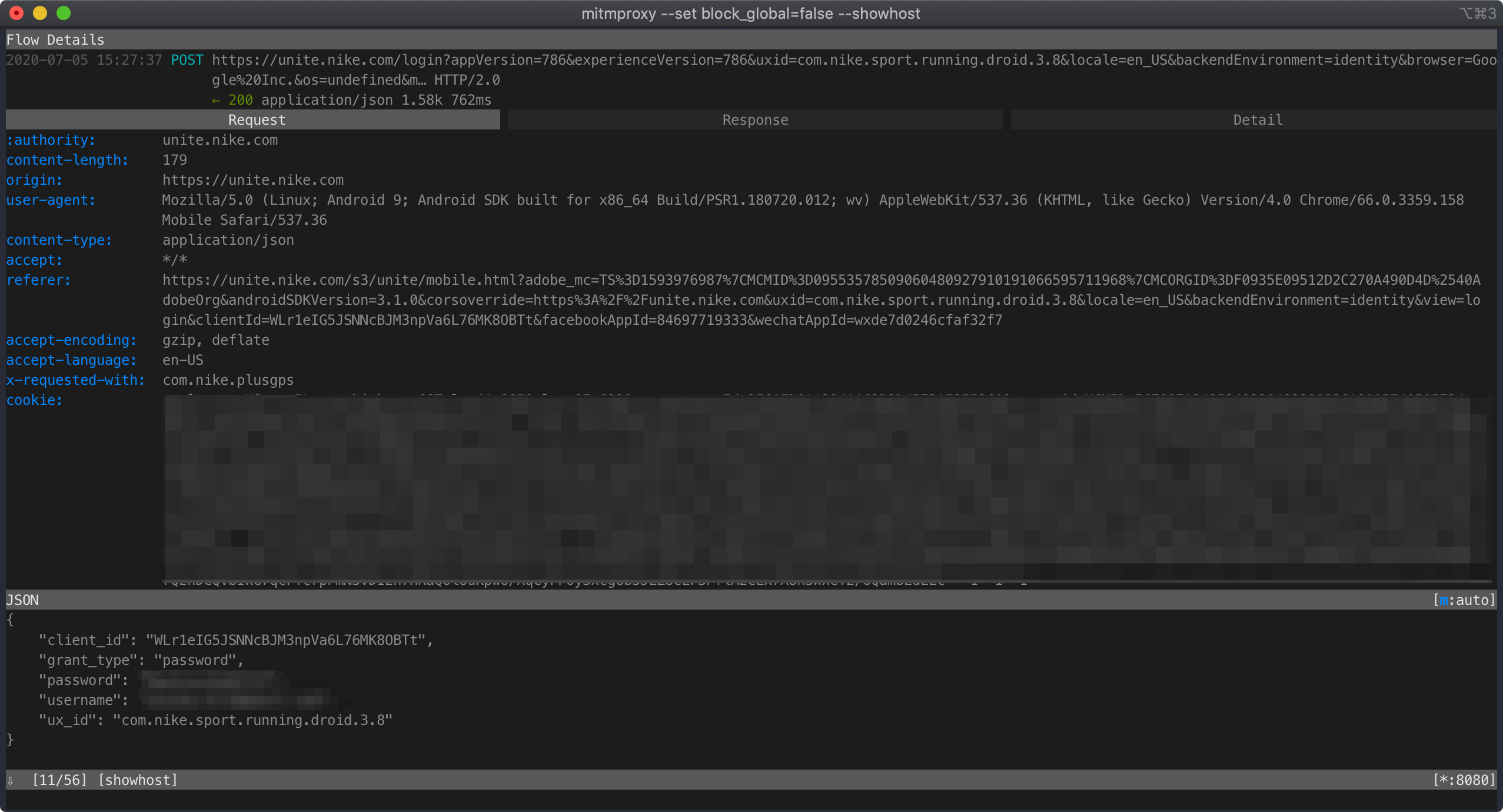

When I tried signing in, I saw this login request:

It looks like a legit login request. But what is that client_id? Everything else seems reasonable and is something we can produce on our own but the client_id seems pretty unique. Where is it coming from?

I checked out a couple of requests before and after this particular API call and couldn’t find the client_id anywhere. It had to be generated within the APK itself. I tried replaying the request a couple of times in mitmproxy and it started failing after 2-3 successful replays. I started receiving this response:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>Access Denied</TITLE>

</HEAD>

<BODY>

<H1>Access Denied</H1>

You don't have permission to access "http://unite.nike.com/login?" on this server.

<P>

Reference #18.2eaf3817.1593493058.26b69156

</BODY>

</HTML>

There was something dynamic in the request and I just had to figure out what. This was the perfect excuse to start snooping inside the NRC app.

By the way, the NRC app makes heavy use of HTML in their app. The login page is actually an HTML document and is loaded from the server. You can access it at this url. More about this later.

Decompile NRC APK

I assume you already downloaded the NRC APK from APKMirror and renamed it to nike.apk. I uploaded the APK to this online version of jadx and decompiled it. We are on the hunt for the client_id and the first thing I do whenever I am trying to find a string, I use grep:

$ grep -r `client_id` ./

Ooo it did output quite a bunch of stuff. This seems to be the most interesting string:

./resources/res/values/strings.xml: <string name="unite_client_id">IFc97q8fSoR84EHfevnzBNivAiT6H+i8vmVZDnCAax/ZjSGxw5ejdekfXtCrzrtJrQfJnj30JeK+MsyruZi8sW6iUBfe//NGZlpQJXUbz8LuPEXnLMAlxKdLV6BrBgKHqNI94nfSHCCr0xW3HOZk/XyFdevndG52zmZR0XXym0yW5d8n/XvLGDCtVyryFLYoYwHYrDC9JZ+GfAacPKE5S437fT9Af+Z/AeZgqPplm9mCaPBoOc0Co4+h3nT8TvXMsU4Vy8pRTuWv0skMU0uwUkq7R/UN06daQ8AkAaYt7KWG0S36tSbHuR03ji7om8ebOJqOzgFyYOp/KfkHkvX5+PVk2lG7lk1hBltitrBND8njmHHIPisC6+W7Ul1an0mRiNTQVFfSJpyNUVvE1D17NQ==</string>

grep also told me where it was being decrypted:

./sources/com/nike/plusgps/login/UniteConfigFactory.java: UniteConfig uniteConfig = new UniteConfig(this.userAgentHeader.getUserAgent(), this.appResources.getString(C5369R.string.unite_experience_id), this.obfuscator.decrypt(this.appResources.getString(C5369R.string.unite_client_id)));

Based on my previous experience with encryption, this seems to be an AES encrypted string. But I need to make sure this is the actual client_id we saw in the request. Time to use Frida and hook into the APK and figure out what the decrypted value of this string is.

Intro to Frida

According to the official website, Frida is a

Dynamic instrumentation toolkit for developers, reverse-engineers, and security researchers.

It allows you to inject scripts in native applications and check out what they are doing under the hood. We will be using it to keep a tab on method inputs in the NRC APK and also make custom calls to different methods. Before we move any further, let’s install Frida first.

Frida installation

There are two parts of Frida (that I am aware of). Frida client and Frida server. The client runs on the host operating system and the server runs of the Android/iOS device. To make testing easier, it is much better to use an Android emulator with Frida.

Installing the client Python packages

For the client-side, there are again two separate packages/libraries we can install using pip. One is called frida and the other is called frida-tools. frida allows us to import and use frida in our code while frida-tools provide us with some really useful command-line tools that will help us in the whole reverse engineering process.

Let’s create a new directory and a virtual environment and install both of these packages. We will work on the server part after this.

$ mkdir nike_project

$ cd nike_project

$ python -m venv env

$ source env/bin/activate

$ pip install frida frida-tools

If everything has been installed and set up correctly, frida-ps -h should output something like this:

$ frida-ps -h

Usage: frida-ps [options]

Options:

--version show program's version number and exit

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-D ID, --device=ID connect to device with the given ID

-U, --usb connect to USB device

-R, --remote connect to remote frida-server

-H HOST, --host=HOST connect to remote frida-server on HOST

-O FILE, --options-file=FILE

text file containing additional command line options

-a, --applications list only applications

-i, --installed include all installed applications

-j, --json output results as JSON

Installing the frida-server on Android

Now we have to install the frida-server on the Android emulator (you can also use your Android device but I prefer the emulator for testing). At the time of writing this article, the latest release of the frida-server is 12.10.4. You can check the latest version at GitHub. Just change the version number in the commands below and they should work:

wget https://github.com/frida/frida/releases/download/12.10.4/frida-server-12.10.4-android-x86_64.xz

unxz frida-server-12.10.4-android-x86_64.xz

adb push frida-server-12.10.4-android-x86_64 /data/local/tmp/frida-server

adb shell chmod 755 /data/local/tmp/frida-server

The above commands downloaded and copied the frida-server to the emulator, now we need to run the server. Open up adb shell:

adb shell

Now run the next command within adb shell:

/data/local/tmp/frida-server &

Frida hooking

Once we have the frida-server running, we can start prepping our JavaScript code for injection.

Prepping initial Frida hook

I checked out the NRC source, followed the breadcrumbs, and found that the decryption magic was happening in the NativeObfuscator file. I found out the process name of the NRC app by running frida-utils -Ua and then wrote the following Python code for testing my hypothesis:

import frida, sys

jscode = """

Java.perform(function (){

var MainActivity = Java.use('com.nike.plusgps.onboarding.login.WelcomeActivity');

var ConfFactory = Java.use('com.nike.plusgps.login.UniteConfigFactory');

var String = Java.use("java.lang.String");

var obfuscator = Java.use("com.nike.clientconfig.NativeObfuscator");

var resources = Java.use("android.content.res.Resources");

var logger = Java.use("com.nike.logger.NopLoggerFactory");

var strRes = "IFc97q8fSoR84EHfevnzBNivAiT6H+i8vmVZDnCAax/ZjSGxw5ejdekfXtCrzrtJrQfJnj30JeK+MsyruZi8sW6iUBfe//NGZlpQJXUbz8LuPEXnLMAlxKdLV6BrBgKHqNI94nfSHCCr0xW3HOZk/XyFdevndG52zmZR0XXym0yW5d8n/XvLGDCtVyryFLYoYwHYrDC9JZ+GfAacPKE5S437fT9Af+Z/AeZgqPplm9mCaPBoOc0Co4+h3nT8TvXMsU4Vy8pRTuWv0skMU0uwUkq7R/UN06daQ8AkAaYt7KWG0S36tSbHuR03ji7om8ebOJqOzgFyYOp/KfkHkvX5+PVk2lG7lk1hBltitrBND8njmHHIPisC6+W7Ul1an0mRiNTQVFfSJpyNUVvE1D17NQ==";

var context = Java.use('android.app.ActivityThread').currentApplication().getApplicationContext();

var log = logger.$new();

var obs = obfuscator.$new(context, log);

console.log(obs.decrypt(strRes));

});

"""

process = frida.get_usb_device().attach('com.nike.plusgps')

script = process.create_script(jscode)

script.load()

I saved this as nike.py and ran it using Python:

$ python nike.py

WLr1eIG5JSNNcBJM3npVa6L76MK8OBTt

The output was exactly what was being sent as part of the request. So it seems like client_id wasn’t being dynamically generated.

This was my first time using Frida for an actual app so I wanted to get some more practice with hooking. So let’s ask frida to place a hook on the decrypt method and print out the input to the method in the console whenever it is called. This is possible by overloading methods using Frida:

jscode = """

setTimeout(function() {

Java.perform(function (){

var obfuscator = Java.use("com.nike.clientconfig.NativeObfuscator");

obfuscator.decrypt.overload('java.lang.String').implementation = function (str){

console.log("******* start ******");

console.log('input str: ' + str);

var output = this.decrypt(str);

console.log('output str: ' + output);

console.log("******* end ******\\n");

return output;

}

});

},0);

"""

Now restart the NRC app and you should start seeing the method calls in the terminal:

******* start ******

input str: FwWEAP2r615reIRlMz45fzIVs4OQqq+IVpyN7d1M1kQ3tYV5Fo6VlOjM435cvAfI0zq+

4M8hWLnqCqpffQqiDbshGTro1zjvyB2D9ow2tGnjXboNcP1f84F0S9RuNZIEobgvmdb4

1SGGuM1ZZxsyMVMjRagwaRTjDGAXb63dSEf2hQjd+40GCElD2qr4OBTZ1b1nY0mLUzHF

7NuLwpxx0HwSN9nyjDaEBRm8NzDpuYOXYPYGkNMsB3nCveLToltwS8impqIEakdOlW3d

Kt9yWH+IaThkwEiDoyv+QPiGJxepMA0jaJH3YxHF8e4exlGoJXYVP1+IKwoZny2W20qQ

0Beg4+7ewL4kw3m+5ttGTd7jRZveDWENoSKnzjb5tUqbHukTcgB2q9o7K3rVFe2iqXxS

rAwxd6VLmKVjB3dF92vm5/Wlxi5mOKFSaiRJMtZg

output str: Basic ZmE2NzJlOTUtYmQwNi00YWZhLWExZjYtYTczNGUzYjhkNmI5OnFidDJ5clJzc

UIzbVFTWQ==

******* end ******

******* start ******

input str: 4sk+vdohXtRY2UkXX2piy+oON0fs/0DjGNfyitJBXc+lIw57oSGIEJLreAPfzf/9Kbdk

Lz2tKJM5wEbDy0LnrAba/lJNTv4semzO9HkudZD4sF/X8O/qwGQEBlQpyjntD11fOMGzIl83ZSC4w8R

vDFCe2DQRMcVB/OCIKFwtcqUJyVLw1W9wJU4AQ733Uabd8KxWOeo/5Hi1B5/mdXlDJD6JnAZJDPhqcl

ECRYW0bPHucvhNtrju/FT2kxlr/x5BhErDSuz2CbWCsLni3zM3Hx+XBvfNHhmINCxBpLdJhF976uHPU

nlaVa0l7y6pV69ir/U8ikMD3Zqis0oBUyZA1wIESnJc+UsS63aNulB+agpMeIGtSVhKiZf8ctjv/lxD

5dvWb4Dp54K5ZAfZ0Zxzrw==

output str: AQzIBimI3XFvsMKXXjFREYpjfS43McGw

******* end ******

So far so good but I need to delve a little bit deeper.

Hooking into JNI calls

In the Android code, I observed that Nike had put all of the encryption and decryption code in a .so file and were using JNI to access that. I found this out because the NativeObfuscator class contained this code:

System.loadLibrary("nike-obfuscator")

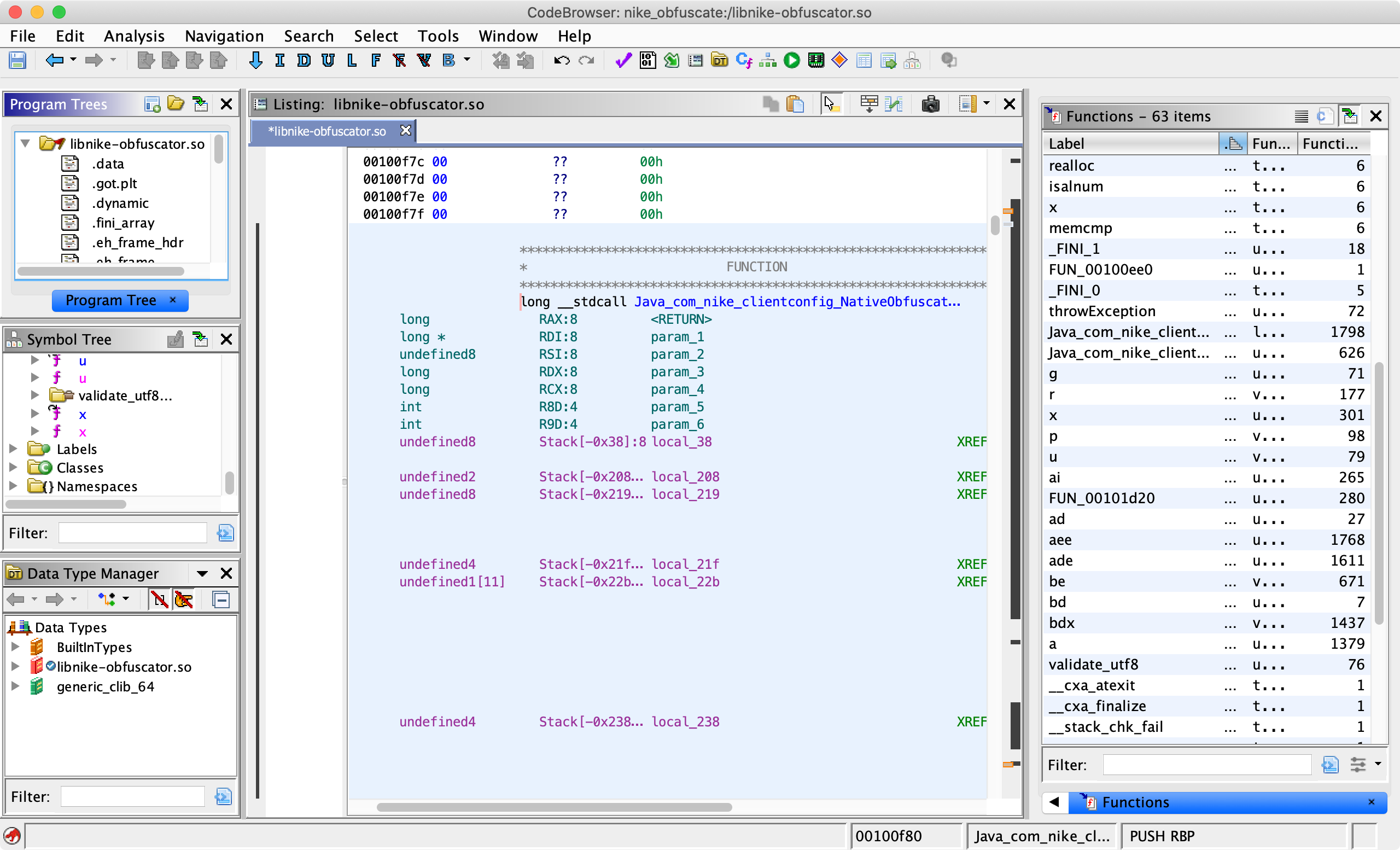

What I also found out was that just like the name suggested, the .so file was obfuscated. Luckily Frida provides us with a super-power to hook into native function calls as well. For that, you have to use the Interceptor and need to know which function calls you want to hook into. If I remember correctly, I found out that the .so file was obfuscated and also the actual functions inside the libnike-obfuscator.so by loading it in Ghidra and letting Ghidra do its magic. You can see the functions list in the right column:

The name of the decryption function was Java_com_nike_clientconfig_NativeObfuscator_decrypt and I hooked into it by using this code:

Interceptor.attach(Module.findExportByName("libnike-obfuscator.so", "Java_com_nike_clientconfig_NativeObfuscator_decrypt"), {

onEnter: function (args)

{

console.log("inside decrypt");

},

onLeave: function(args)

{

console.log("outside decrypt");

}

});

I also had to adjust my nike.py code to make sure that frida relaunches the NRC app on each script execution because the decryption stuff happens right when the APK loads up for the first time. I did that by replaced the code at the bottom with this:

app_name = 'com.nike.plusgps'

device = frida.get_usb_device()

pid = device.spawn(app_name)

device.resume(pid)

time.sleep(1)

process = device.attach(pid)

script = process.create_script(jscode)

script.load()

sys.stdin.read()

The arguments to functions in .so are actually memory pointers and we can print out the value at that pointer by modifying our Interceptor code:

Interceptor.attach(Module.findExportByName("libnike-obfuscator.so", "Java_com_nike_clientconfig_NativeObfuscator_decrypt"), {

onEnter: function (args)

{

console.log("inside decrypt");

var data = Memory.readByteArray(args[0], 10);

console.log("Memory data: ");

console.log(data);

},

onLeave: function(args)

{

console.log("outside decrypt");

}

});

I don’t know the size of the input so I manually put in 10 in this case. The output was similar for all function calls:

inside decrypt

Memory data:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0123456789ABCDEF

00000000 10 43 5f c6 4a 72 00 00 00 4c .C_.Jr...L

outside decrypt

This was good, my theory regarding client_id being static was correct and I had proved that by hooking onto the actual Java method calls. I tried to go through the obfuscated .so code using Ghidra but soon gave up. The pointer addresses were scrambled, the inputs were not at the actual input param pointers and the whole thing was a mess. I realized that there was not use for me to actually go through the effort because there wasn’t anything dynamic that was being generated by that file. I only cared about the encrypted and decrypted strings and I had all of those by just hooking to Java code.

This is where my APK reverse engineering journey ended and I decided to put “reverse engineering the .so file” on the backburner. But, I wasn’t done for this project. I still had to figure out how the login works so that I can create a tool for automatic token and activity extraction.

Note: There is also the jnitrace program based on Frida that is supposed to print all JNI calls but NRC was crashing whenever I tried using jnitrace. And for those of you who might actually want some challenge, try reverse engineering the .so file. There was a call to android.content.pm.Signature in it and I believe that the code might be using something from there to get the key for AES decryption.

Reversing login endpoint

Remember I told you in the beginning that the NRC app makes use of HTML and loads the login page from their server? I continued the rest of my testing on that endpoint. I observed the actual request in more detail and saw certain cookies which seemed interesting. There was an _abck cookie and another cookie which I am forgetting now. I did some research online and found out that they were used by Akamai Bot Manager to filter out bots. That is why the API endpoint replay was failing as well.

I looked around the internet hoping that someone would have managed to reverse engineer the bot manager but it is a cat and mouse game. Those who have reverse-engineered it don’t put all their research online because then Akamai will simply patch it. There were certain repos on GitHub that were supposed to work but they were updated a long time ago. I wasn’t able to find any repo that either worked or had actual details on how to use it.

Now we are getting outside the scope of this article so I will just give you a summary of what I did next. The primary issue was that I need access to the Bearer tokens in an automated fashion so that I could eventually use it to make API calls to Nike. I already knew how to manually extract it but wanted to provide users with an automated tool. I searched around and found out a different URL that could be automated using Selenium, seleniumwire, and geckodriver.

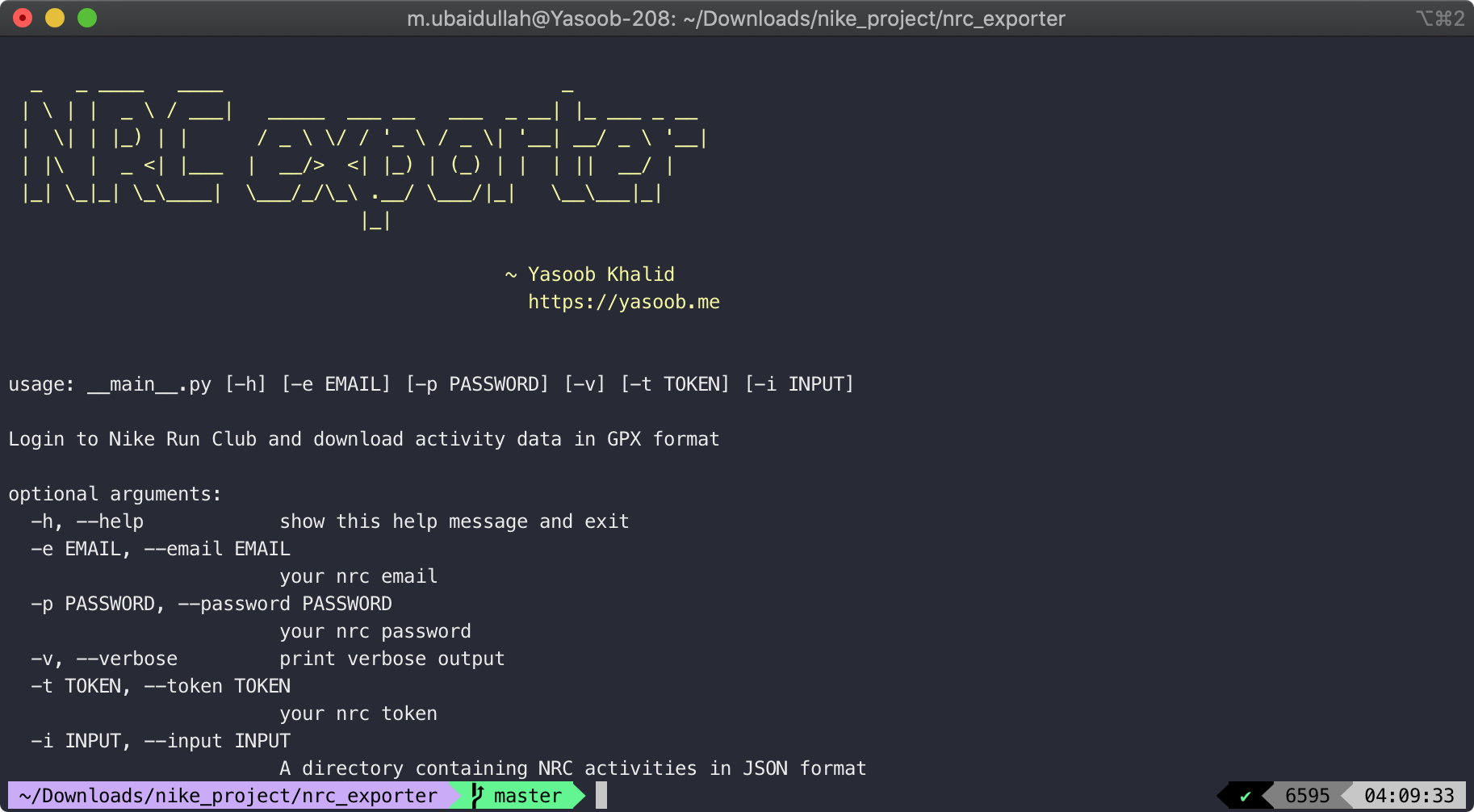

And after some sleepless nights, I whipped up a script called nrc-exporter.

It allows you to export your run data from Nike and convert it to GPX format. It is still in its infancy and there are quite a few rough edges but it works for my purposes. If you are interested, please feel free to improve it and submit pull requests. I am always happy to receive contributions.

Conclusion

I hope you learned something new in this article. I for sure learned quite a lot of new stuff. It is always exciting to see what different APKs are doing under the hood. This article barely scratched the surface of what Frida is capable of. If you want to learn more about it, check out the resources linked at the end of this article. As for me and my interest in APK reversing?

The token automation used by nrc-exporter will most probably be blocked as soon as I publish this article but now you know how to generate it manually so it is all good.

Please show the nrc-exporter some star love on GitHub and I will see you with an even more interesting article in the future. Take care and stay safe! 👋 ❤️

Nick

Yasoob

In reply to Nick

Shiv

Andrew

Andrew